Australia is a great place for business. However, like in any other country, there are things you need to know about doing business onshore. This article clarifies and answers your main questions and tell you what else you need to know about setting up and doing business in Australia, so you can make informed decisions.

In this article:

- Foreign Investment Landscape in Australia

- Foreign Investment Approval Process

- Company Types & Tax Obligations

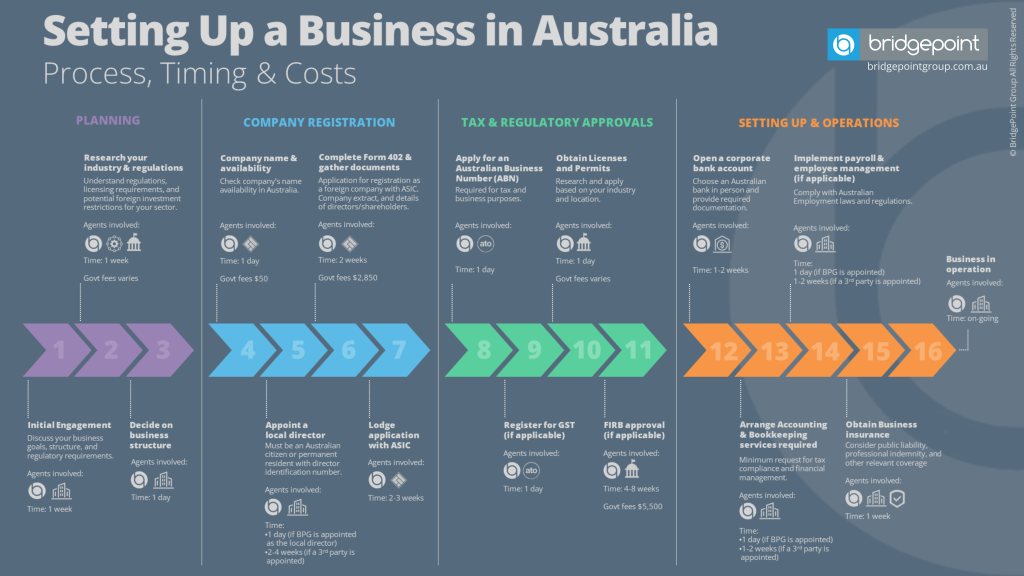

- Process, Timing & Costs of Setting Up a Business

- Accounting Requirements

- Legal Landscape

- Doing Business in Australia with BridgePoint Group

Foreign Investment in Australia

The Australian Government values foreign investment that aligns with its national interests, recognising its significant contribution to Australia’s economic growth and prosperity.

Foreign investment within Australia falls under the regulation of the Foreign Acquisitions and Takeovers Act 1975 (Cth) (FATA), its associated regulations, and Australia’s Foreign Investment Review Board Policy (FIRB Policy).

A controlling (or substantial) foreign interest is established if one foreign person (along with any associates) possesses 15% or more of the ownership or voting rights. Similarly, it arises when multiple foreign individuals (or any associates) collectively possess 40% or more of the ownership or voting rights in any corporation, business, or trust.

The administration of FATA and FIRB Policy rests with the Australian Federal Treasurer, supported by the Foreign Investment Review Board (FIRB). Empowered by FATA and FIRB Policy, the Treasurer holds the authority to decline specific foreign investment proposals, impose conditions upon them, and enact various other measures if they are deemed contrary to the national interest or pose risks to national security.

Certain foreign investment proposals necessitate notification to FIRB and require approval from the Treasurer prior to their execution. Typically, the majority of applications do not raise concerns related to national interest or security and consequently receive approval.

Foreign Persons

According to the Foreign Acquisitions and Takeovers Act (FATA), a ‘foreign person’ is:

- An individual who isn’t typically a resident in Australia.

- A foreign government or investor representing a foreign government.

- A corporation, trustee of a trust, or general partner of a limited partnership where an individual not typically residing in Australia, a foreign corporation, or a foreign government holds an equity interest of at least 20%.

- A corporation, trustee of a trust, or general partner of a limited partnership where two or more foreign persons hold a combined equity interest of at least 40%.

Doing Business in Australia in Sensitive Sectors

Limitations are imposed on foreign investment into sensitive industrial sectors that mirror community concerns and issues concerning the national interest. Restrictions are enforced on foreign investment within sectors including Real Estate, Media, Telecommunications, Transport, Defense-related industries, Critical Infrastructure, National Security Companies, Security Land, Encryption and Security Technologies, Communication Systems, and the Extraction of Uranium or Plutonium, or the Operation of a Nuclear Facility. Special regulations are applicable in Agribusiness to enterprises or nationals of United States of America, Chile or New Zealand.

How foreign investors gets the Green Light (or Red Flag)

The Foreign Investment Review Board (FIRB Policy) plays a crucial role in safeguarding Australia’s national interest when it comes to foreign acquisitions of land, businesses, and other assets. Its approval hinges on four key factors:

- National security: Does the investment pose any national security risks, like giving foreign entities undue influence over sensitive infrastructure or technologies?

- Competition: Could the acquisition create an unfair monopoly or stifle competition in a particular industry?

- Taxation: Will the investment comply with Australian tax laws and contribute its fair share to the economy?

- Employment: Will the investment create or preserve jobs for Australians?

For land acquisitions, the FIRB also considers factors like the land’s intended use, its potential impact on Australian residents, and whether it’s deemed “vacant” residential land (subject to additional scrutiny and potential vacancy fees).

The FIRB’s goal is to ensure that foreign investment benefits Australia, not just the foreign investor. So, while it might not always rubber-stamp every proposal, its thorough review process helps maintain a balance between attracting foreign capital and protecting Australia’s strategic and economic interests.

Doing Business in Australia – FIRB Approval Process

The processing time for standard applications is 30 days and some of the key steps are:

- Determine if FIRB approval is required: This depends on the transaction value, the asset type (land, business, rural land), the foreign investor type (individual, government, etc.), and if the target business involves any sensitive sectors.

- Lodge an application: You need to provide details about the transaction, parties involved, and potential national interest impacts. Some specific investments are eligible for exemptions.

- Assessment: FIRB meticulously examines the transaction against four key factors.

- Treasurer’s decision: The FIRB makes a recommendation to the Australian Treasurer to approve, reject, or approve with conditions. However, the Treasurer has the ultimate say, considering the FIRB’s recommendation and broader national interests.

- Post-approval compliance: If approved with conditions, the foreign investor must adhere to them, potentially including divesting specific assets or implementing security measures. The FIRB may monitor compliance and even impose penalties for non-compliance.

- Exemptions: Pension funds, government bodies, and certain types of entities, as well as low-risk transactions like buying residential property below the threshold, may be exempt from review.

Establishing a business presence in Australia

Business in Australia may be conducted by a person as a sole trader (individual), a company, a joint venture, a partnership, a trustee of a trust, a registered foreign company, or an Australian subsidiary of a foreign company.

A foreign investor may choose any of these options.

Different business structures have different legal features, responsibilities, and tax consequences. Therefore, a foreign investor who wants to establish a business structure in Australia will have to think carefully about which structure suits their goals and needs. This section gives a general overview of these business structures and explains their main tax obligations.

Company Types

In Australia, the predominant form of business organisation is a company limited by shares. These can be classified into two types: proprietary or public. A business can choose to register as either a proprietary or a public company depending on its needs and goals.

Proprietary Limited Company (Pty Ltd)

- Ownership: Can have a maximum of 50 non-employee shareholders.

- Shares: Shares are not publicly offered and cannot be traded on a stock exchange.

- Liability: Shareholders have limited liability

- Reporting Requirements: Large proprietary companies must lodge audited financial reports with the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC). Small proprietary companies may not be required to lodge audited financial reports.

- Suitability: Suitable for small to medium-sized businesses that want the benefits of limited liability without the complexities of public company regulation.

Public Company (Limited)

- Ownership: Can have an unlimited number of shareholders, including the public.

- Shares: Shares can be offered to the public and traded on a stock exchange.

- Liability: Shareholders have limited liability

- Reporting Requirements: Public companies must lodge audited financial reports with ASIC and comply with stricter corporate governance requirements.

- Suitability: Suitable for large businesses that want to raise capital through public share offerings and have the potential for growth and expansion. Public companies are subject to greater regulatory scrutiny than proprietary companies

Types of entities and tax obligations

Sole Trader

A foreign person who operates a business in Australia as a sole trader has personal liability for all the debts and obligations of the business. A sole trader must register a business name if they want to use a name that is different from their own. This type of entity can have employees in their business, but they cannot be an employee of their own business. A sole trader is also responsible for paying super guarantee for their employees, which is a compulsory superannuation contribution. A sole trader does not have to pay super guarantee for themselves, but they can make voluntary super contributions to save for their retirement.

Tax Obligations

- Use their individual Tax File Number to lodge their tax return and report their business income and expenses in the section for business items (there is no separate tax returns for sole traders).

- Eligible for an Australian Business Number (ABN) and use it for all their business activities.

- Register for Goods and Services Tax (GST) if:

- annual GST turnover is $75,000 or more

- provide taxi, limousine or ride-sourcing services (regardless of their GST turnover)

- want to claim fuel tax credits

- Lodge business activity statements, for example if they are registered for GST, have employer obligations such as Pay As You Go withholding (PAYGW), or have PAYG instalments (PAYGI).

- Pay tax on all their income, including their business income, at their individual tax rate.

- Can choose to make, or may be required to make, PAYG instalments to prepay their income tax.

- Can claim a deduction for any personal super contributions they make after notifying their fund of their intention to claim a tax deduction

Partnership

A partnership is a business arrangement where two or more individuals or entities work together as partners with the intention of making profit. Partnerships can be created by agreements or by actions. They are regulated by State and Territory laws, not by Federal law, and usually have two to 20 members, with some exceptions. Partnerships do not have a separate legal identity. Like sole traders, partners are personally responsible for all the debts and obligations of the business, both individually and collectively. In some States, there is an option to set up a limited liability partnership to provide some protection to the partners.

Tax Obligations

- Have a TFN and use it to lodge an annual partnership return that shows its business income and expenses and how they are shared among the partners.

- Obtain an ABN and use it for all its business transactions.

- Register for GST if it either: makes $75,000 ($150,000 for not-for-profit organisations) or more in annual GST turnover; offers taxi, limousine or ride-sourcing services (regardless of GST turnover); wants to claim fuel tax credits.

- May need to lodge business activity statements, for example if it is registered for GST, has employer obligations such as PAYG withholding.

- It does not pay tax itself. Each partner reports their portion of the partnership income and gains or losses in their own tax return and is responsible for any tax that may be due on that income.

- The amounts you withdraw from a partnership are not considered wages for tax purposes. This may mean that the partnership income you must pay tax on is different to the amount of your drawings.

Trust

You can also do business in Australia as a trust. A trust is a legal arrangement in which one person (the ‘trustee’) holds the assets for the benefit of others (the ‘beneficiaries’). A trustee can be an individual or a company. Often, businesses use unit trusts or discretionary trusts as part of their structure. A trust is not a separate legal entity, but a company may act as the trustee to (among other things), ringfence the risk of liability.

Tax Obligations

- Lodge its own tax return and pay superannuation liabilities.

- Obtain its own TFN.

- Obtain an ABN if it operates a business in Australia.

- Register for GST if it: has annual GST turnover of $75,000 ($150,000 for not-for-profit organisations) or more; offers taxi, limousine or ride-sourcing services (regardless of GST turnover); wishes to claim fuel tax credits.

- Lodge business activity statements, for example if it is registered for GST, has employer obligations such as PAYG withholding.

- Lodge an annual tax return.

- Pay superannuation for eligible employees.

- Trustee of the Trust may pay tax on any undistributed profits at the relevant tax rate.

Company

A company who does business in Australia is an independent legal entity that has its own tax and superannuation responsibilities, is managed by its directors and is owned by its shareholders. A company’s income and assets are its own property, not that of the shareholders. A company can share profits with its shareholders through dividends and may be able to add ‘franking credits’ (also referred to as imputation credits) to those dividends. This enables shareholders to receive credit for the tax already paid by the company, thereby avoiding ‘double taxation’. While a company typically offers good levels of asset protection, in certain instances, its directors can be personally liable for their actions. All directors are legally obliged to confirm their identity and apply for a director identification number (DIN) before being appointed.

Tax Obligations

- Pay its own tax and superannuation liabilities.

- Obtain its own TFN.

- Get an ACN when registered under the Corporations Act 2001, it can also get an ABN if it operates a business in Australia.

- Register for GST if it: has annual GST turnover of $75,000 ($150,000 for not-for-profit organisations) or more; offers taxi, limousine or ride-sourcing services (regardless of GST turnover); wishes to claim fuel tax credits.

- Lodge business activity statements, for example if it is registered for GST, has employer obligations such as PAYG withholding, or has PAYG instalments.

- Lodge an annual company tax return.

- May be required to pay income tax by instalments through the PAYG instalments system.

- Pay tax at its relevant company tax rate.

- Pay super guarantee for any eligible workers (this includes any company directors).

- Issue distribution statements to any shareholders it pays a dividend to.

Entities subject to comparable Company taxation

Registered Foreign Company

A foreign company can operate in Australia without setting up an Australian business entity. However, the foreign company must register as a foreign company in Australia. This requires filling out and submitting the relevant registration forms to ASIC. Upon registration, an Australian Registered Body Number (ARBN) will be allocated to the foreign company.

The foreign company conducting business in Australia is commonly known as a branch office in Australia. The Branch of a registered foreign company is not a separate legal entity. The foreign company is responsible for any liabilities. Foreign companies must appoint a local agent, who can be personally liable for any penalties imposed on a foreign company.

Subsidiary

A foreign company can also operate in Australia by registering a new Australian company with ASIC. This also requires filling out and submitting the relevant registration forms to ASIC. Companies incorporated in Australia will be issued with an Australian Company Number (ACN). The new Australian company conducting business in Australia is a separate legal entity. The subsidiaries are wholly or partly owned by their foreign parent companies.

Joint Venture

Foreign investors can engage in joint ventures with Australian entities. They commonly involve multiple companies or individuals collaborating on a particular endeavour. These ventures are often specific to a project and can take the form of either an incorporated joint venture, where participants jointly establish a company, or an unincorporated arrangement.

Thin Capitalisation Rules

The Thin Capitalisation Rules aim to prevent multinational companies from artificially inflating their debt expenses to reduce their taxable income in Australia. These rules disallow debt deductions which exceed certain limits. The rules apply to outward investors and to foreign controlled Australian entities or foreign entities carrying on business or other income producing activities in Australia through a permanent establishment (inward investors). The thin capitalisation rules apply when debt deductions (interest and other debt costs) are at least $2 million on an associate level.

Under the existing rules, the Safe harbour test disallows debt deductions to the extent that borrowings exceed the safe harbour ratio (60% of the value of an entity’s net Australian assets or a debt-to-equity ratio of 1.5:1). Where borrowings exceed these safe harbour amounts, the following alternative tests are available:

- Arm’s length debt test: this test allows taxpayers to determine a notional level of debt that would be loaned to the Australian business on an arm’s length basis.

- Worldwide gearing test: taxpayers can gear their Australian business to similar levels to the global gearing level.

- A Bill has been introduced to Parliament with proposed amendments. The new regime applies to income years commencing on or after 1 July 2023 and contains three new tests to replace the current tests:

- Fixed ratio test: this is the default test which limits debt deductions to 30% of an entity’s earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation (EBITDA).

- Group ratio test: this is an earnings based test allowing an entity in a group to claim net debt deductions proportionate to the group’s debt divided by its earnings.

- Third party debt test: only allows debt deductions related to genuine third-party debts which fund Australian operations.

- Financial entities and Authorised Deposit-taking Institutions (ADIs) would continue to be subject to the existing rules (except for the arm’s length debt test).

Transfer Pricing Rules

The Australian Transfer Pricing Rules impose arm’s length terms and conditions on Australian companies, branches, partnerships and trusts undertaking cross border transactions with international related parties. The rules seek to ensure that the appropriate level of profit is reported and taxed in Australia and prevent arrangements which artificially shift profits between countries. Transfer pricing applies to transactions such as goods, services, royalties, licence fees, loans and capital transactions.

Taxpayers with related party transactions in excess of $2 million are required to disclose these transactions to the ATO in their tax return. Transfer pricing documentation should be in place to demonstrate that the transactions have been conducted on arm’s length terms. Significant Global Entity (SGEs), broadly global parent entities or a member of that global parent entity’s group with annual global income of A$1 billion or more, have additional lodgement obligations with the ATO.

Setting up a company in Australia

Company Registration

The process of establishing an Australian company involves selecting a name that is available and meets registration requirements, and the completion of the appropriate application form to be submitted to ASIC. ASIC will only proceed with company registration if the chosen name is available.

The application form requires details about the proposed company, such as the registered office and principal business location in Australia, the names of the shareholders and share structure and the intended directors or secretaries of the company. Upon lodgment of the relevant form with ASIC, a company is typically incorporated within a 24-hour timeframe.

Any overseas company looking to establish an Australian operation must also comply with some additional regulatory requirements, such as the following:

- Appoint a Resident Director: An overseas company must appoint at least one director who is ordinarily resident in Australia. This individual must have a good understanding of Australian corporate law and business practices. Before assuming the role of a director, an individual must possess or have applied for a Director Identification Number (DIN). This unique identifier is granted to a director who has undergone identity verification through the Australian Business Registry Service. The DIN aims to deter the use of false or deceptive director identities.

- Tax File Number (TFN) Registration: An Australian subsidiary must obtain a TFN from the ATO. The TFN is used for tax purposes and must be provided to the ATO when lodging tax returns.

- PAYG Withholding Tax: The entity must withhold PAYG withholding tax from the salaries of its employees.

- Bank Account: The Australian subsidiary will need to open a bank account in Australia. This will allow the company to receive and make payments.

- Public Offer: Every Australian company must appoint a public officer – the contact person for ASIC and the ATO.

- Company Secretary: While not mandatory, it is highly recommended for an Australian subsidiary to appoint a company secretary – responsible for ensuring that the company complies with its legal obligations.

- Substituted Accounting Period (SAP): An overseas company can apply for a SAP if its financial year does not align with the Australian Financial Year (in Australia, the FY is 1 July to 30 June). A SAP allows the company to prepare its financial statements in accordance with its own financial year.

- Insurance Requirements: An Australian subsidiary will need to obtain appropriate insurance to protect its assets and its employees. The specific insurance requirements will depend on the nature of the business. However, any entity that employs staff must have workers’ compensation insurance, to cover workers that are injured on the job.

- Superannuation Guarantee (SG): The Australian subsidiary must pay superannuation on behalf of its employees. It is a compulsory contribution to an employee’s superannuation fund. Consequences of not paying super to employees can be severe, both financially and reputationally. Businesses should take all necessary steps to ensure that they are complying with their SG obligations.

Accounting Requirements

A comprehensive set of rules for company accounts and audit processes is set out in the Corporations Act. These rules apply exclusively to companies that are registered in Australia.

Financial Reporting

All disclosing entities, including public companies, large proprietary companies, and registered managed investment schemes, are required to prepare financial statements that comply with the Australian Accounting Standards (AASB). The AASB are based on International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), and they set out the requirements for preparing, presenting, and disclosing financial information. The financial reports must consist of:

- Statement of financial position

- Statement of profit and loss

- Statement of cash flow

- Statement of change in equity

- Notes to the financial statements

- Directors’ declaration

- Directors’ report

The financial reports must be prepared for each financial year, and they must be lodged with the ASIC within four months of the end of the financial year.

Record Keeping

All companies are required to keep financial records that accurately record their financial transactions and which would enable the preparation of financial statements and the audit of those financial statements. The financial records must be kept for a period of at least seven years.

Audit

Public companies, large proprietary companies, and any other company that ASIC directs, are required to have their financial reports audited by an independent auditor. The auditor is responsible for expressing an opinion on whether the financial report is free from material misstatement. The auditor’s report must be lodged with ASIC within four months of the end of the financial year.

Small Proprietary Companies

Small proprietary companies are not required to have their financial reports audited. However, they are still required to prepare financial statements and keep financial records. The financial statements must be prepared for each financial year, and they must be kept for a period of at least seven years.

Penalties for Non-compliance

Failure to comply with the requirements relating to company accounts and audit procedures can result in penalties, including fines and imprisonment. ASIC also has the power to disqualify directors of companies that fail to comply with these requirements.

Legal Landscape for businesses in Australia

Corporate Law

The Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) is the main legislation that regulates all corporations in Australia. It outlines the procedures for the creation, management, and dissolution of companies, as well as the responsibilities of directors and other officers. The Act also covers a broad range of other topics, such as financial reporting, takeovers, and mergers. Some of the main features of the Corporations Act 2001 are:

Company Formation

This act lays down the groundwork for establishing a company in Australia. It defines the prerequisites, like the minimum number of shareholders, the necessity for a registered office, and the appointment of directors.

Corporate Management

It outlines the powers and duties of directors and other company officers. Additionally, it sets rules for general meetings, shareholder voting procedures, and dividend distribution.

Financial Reporting

The Act mandates companies to prepare and submit various financial reports, including annual and half-yearly reports, profit and loss statements, ensuring transparency and accountability.

Takeovers and Mergers

Regulations for takeovers and mergers fall under this Act, emphasising the need for shareholder approval and the standards for disclosure and transparency throughout these processes.

Company dissolution

When it comes to winding up a company, this act dictates the necessary procedures, such as appointing liquidators and distributing assets among creditors and shareholders.

Obligations of Directors:

- Duty of Care and Diligence: Directors are expected to exercise reasonable care and diligence in their decision-making processes.

- Acting in Good Faith: They must act in the best interests of the company and its shareholders, showing utmost good faith in their actions.

- Avoid Conflict of Interest: Directors are obliged to steer clear of any conflicts between their personal interests and their duties to the company.

- Disclosure of Personal Interests: Any personal interests that could significantly impact the company’s affairs must be disclosed by the directors.

Competition Law

The Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (CCA) is the main source of Australia’s competition laws, which are similar to those in North America and Europe. The CCA regulates the conduct of businesses and individuals to promote fair and effective competition in the Australian market.

The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) is the agency responsible for administering and enforcing the CCA. The CCA contains a number of provisions that are designed to promote competition and protect consumers.

Penalties for violating competition law are severe, with fines. For some offences by companies, up to a maximum of $10 million, 3 times the contravention gain or 10% of the Australian business group’s annual turnover in the previous 12 months; and for individuals for some offences, up to $500,000. Here are some of the key prohibitions of the CCA:

Cartel conduct

Cartel conduct is the most serious form of anti-competitive conduct. It involves businesses colluding with each other to fix prices, rig bids, share markets, or control output. Cartel conduct can harm consumers by leading to higher prices, lower quality products and services, and less choice.

Misuse of market power

Businesses with a substantial degree of market power have a special responsibility to not use that power in a way that is anti-competitive. This includes not engaging in predatory pricing, exclusive dealing, or refusals to supply.

Misleading or deceptive conduct

Businesses must not engage in misleading or deceptive conduct in relation to the supply or acquisition of goods or services. This includes making false or misleading statements, engaging in bait and switch tactics, and using unfair terms and conditions.

Unconscionable conduct

Businesses must not engage in unconscionable conduct. This means that they must not exploit a special advantage or vulnerability of a consumer to the detriment of that consumer. Unconscionable conduct can include taking advantage of a consumer’s lack of understanding, taking advantage of a consumer’s financial situation, or using high-pressure sales tactics.

Product safety

Businesses must not supply unsafe goods or services. This includes goods that do not comply with safety standards, goods that are defective, and goods that are not fit for the purpose for which they are sold.

Price discrimination

Businesses must not engage in price discrimination. This means that they must not charge different prices for the same goods or services to different customers unless there is a reasonable justification for doing so.

Restricted horizontal agreements

Restricted horizontal agreements are agreements between businesses at the same level of the supply chain that may restrict competition. Examples of restricted horizontal agreements include agreements to fix prices, share markets, or limit output.

Restricted vertical agreements

Restricted vertical agreements are agreements between businesses at different levels of the supply chain that may restrict competition. Examples of restricted vertical agreements include agreements to fix resale prices, limit output, or grant exclusive territories.

Resale price maintenance

Resale price maintenance (RPM) is the practice of a supplier imposing a minimum price on its customers for the resale of its goods or services. RPM can harm consumers by leading to higher prices and less choice.

Refusal to supply

A business with a substantial degree of market power must not refuse to supply goods or services to another business if that refusal would be likely to substantially lessen competition.

Exclusive dealing

A business with a substantial degree of market power must not enter into an exclusive dealing arrangement with another business if that arrangement would be likely to substantially lessen competition.

Predatory pricing

Predatory pricing is the practice of charging a price that is below cost for a prolonged period with the intention of driving competitors out of the market. It can harm consumers by leading to higher prices in the long run.

Consumer Protection

The Australian Consumer Law (ACL) is a part of the CCA that regulates consumer rights and obligations in Australia. It is the single and national law, applied in all states and territories, although additional consumer protection and fair-trading laws in each state and territory may vary from one jurisdiction to another.

The ACL covers issues such as unfair contract terms in standard form contracts, statutory ‘guarantees’ for goods and services supplied to ‘consumers’ and product safety standards. The ACL also contains a number of provisions that are designed to protect consumers and promote fair trading. Here are some of the key prohibitions of the ACL:

Misleading or deceptive conduct

Businesses must not engage in misleading or deceptive conduct in relation to the supply or acquisition of goods or services. This includes making false or misleading statements, engaging in bait and switch tactics, and using unfair terms and conditions.

Unconscionable conduct

Businesses must not engage in unconscionable conduct. This means that they must not exploit a special advantage or vulnerability of a consumer to the detriment of that consumer. Unconscionable conduct can include taking advantage of a consumer’s lack of understanding, taking advantage of a consumer’s financial situation, or using high-pressure sales tactics.

Unsafe products

Businesses must not supply unsafe goods or services. This includes goods that do not comply with safety standards, goods that are defective, and goods that are not fit for the purpose for which they are sold.

False or misleading representations

Businesses must not make false or misleading representations about goods or services. This includes making false or misleading statements about the price, quality, or performance of goods or services.

Component pricing

Businesses must not engage in component pricing. This means that they must not break down the price of a good or service into its individual components and charge separately for each component.

Unsolicited supplies

Businesses must not send unsolicited goods or services to consumers. This includes sending goods or services to consumers who have not requested them, or who have requested them to be stopped.

False or misleading country of origin claims

Businesses must not make false or misleading claims about the country of origin of goods or services. This includes claiming that a good or service is made in Australia when it is not.

Pyramid selling

Businesses must not engage in pyramid selling. This is a type of selling where consumers are encouraged to recruit new participants into the scheme in order to earn money, rather than from the sale of goods or services.

Lay-by agreements

Businesses must not enter into lay-by agreements with consumers that are unfair or unconscionable. This includes agreements with unreasonable lay-by periods, excessive lay-by fees, or unfair forfeiture provisions.

Repair and replacement

Businesses must provide consumers with a repair or replacement for goods that are defective or do not comply with the guarantee. The consumer is entitled to choose which remedy they prefer.

Refunds

Consumers are entitled to a refund for goods that are defective or do not comply with the guarantee if they are unable to be repaired or replaced. The refund must be provided within a reasonable time.

Compensation

Consumers may be entitled to compensation for losses they have suffered as a result of defective or non-compliant goods or services. This may include compensation for the cost of repairs, replacement, or the purchase of a new product, as well as for any other losses incurred.

Employment Law

The Fair Work Act (2009) is the name of the federal legislation that regulates the employment relationship in Australia (except for private sector employers and employees in Western Australia). The Fair Work Act covers matters such as minimum wages, unfair dismissal, industrial action, enterprise bargaining and workplace rights and obligations.

According to the Fair Work Act, the minimum employment terms and conditions in Australia enforces the following:

Maximum Weekly Hours

An employee’s ordinary hours of work must not exceed 38 hours per week, averaged over a 52-week period. However, there are some exceptions to this rule, such as for employees who work in certain industries or who work irregular hours.

Requests for Flexible Working Arrangements

Employees have the right to request a flexible working arrangement from their employer. The employer must consider the request seriously and give reasons if they refuse it.

Offers and Requests to Convert from Casual to Permanent Employment

Employees who have worked for their employer for at least 12 months as a casual employee have the right to request to convert to permanent employment. The employer must consider the request seriously and give reasons if they refuse it.

Parental Leave and Related Entitlements

Employees who are primary carers of a child are entitled to take parental leave from their employer. Parental leave can be taken for up to 12 months, and employees can choose to take it all at once or in blocks.

Annual Leave

Employees are entitled to at least four weeks of paid annual leave per year. Annual leave must be accrued at a rate of at least 9.57% of the employee’s ordinary earnings.

Community Service Leave

Employees are entitled to take community service leave to volunteer for emergency services or to participate in jury duty. Community service leave can be taken for up to 15 days per year.

Personal/Carer’s Leave, Compassionate Leave and Family and Domestic Violence Leave

Employees are entitled to take personal/carer’s leave, compassionate leave, and family and domestic violence leave. Personal/carer’s leave can be taken for up to 10 days per year for illness or injury, and compassionate leave can be taken for up to two days per year for bereavement. Family and domestic violence leave can be taken for up to five days per year.

Long Service Leave

Employees who have worked for their employer for at least 10 years are entitled to take long service leave. Long service leave can be taken for up to 13 weeks, and employees can choose to take it all at once or in blocks.

Public Holidays

Employees are entitled to be paid for all public holidays that occur on a day they would normally be working.

Notice of Termination and Redundancy Pay

Employees must be given a certain amount of notice of termination depending on their length of service. Redundancy pay is also payable to employees who are made redundant.

Fair Work Information Statement and Casual Employment Information Statement

Employers must provide all employees with a Fair Work Information Statement (FWIS) and casual employees with a Casual Employment Information Statement (CEIS). The FWIS and CEIS outline the employee’s rights and entitlements under the Fair Work Act.

Intellectual Property

Australia’s legislation offers extensive safeguards for intellectual property, encompassing copyright, patents for inventions, trade names and trademarks, domain names, trade secrets, confidential information, and registered designs.

These laws align with Australia’s international trade and treaty obligations, exemplified by compliance with agreements such as the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and the TRIPS Agreement. Moreover, they have undergone adjustments following the free trade agreement between Australia and the USA.

The regulation of intellectual property rights in Australia predominantly occurs through provisions outlined in Acts like the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth), Patents Act 1990 (Cth), Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth), Designs Act 2003 (Cth), Plant Breeder’s Rights Act 1994 (Cth), and Circuit Layouts Act 1989 (Cth).

Trade Marks

Australia’s legislation offers extensive safeguards for intellectual property, encompassing copyright, patents for inventions, trade names and trademarks, domain names, trade secrets, confidential information, and registered designs.

These laws align with Australia’s international trade and treaty obligations, exemplified by compliance with agreements such as the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and the TRIPS Agreement. Moreover, they have undergone adjustments following the free trade agreement between Australia and the USA.

The regulation of intellectual property rights in Australia predominantly occurs through provisions outlined in Acts like the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth), Patents Act 1990 (Cth), Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth), Designs Act 2003 (Cth), Plant Breeder’s Rights Act 1994 (Cth), and Circuit Layouts Act 1989 (Cth).

Patents

Australia belongs to the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT), which provides a system for obtaining patent protection in multiple countries. The Patents Act 1990 (Cth) governs the patent system in Australia and IP Australia’s Patents Office is responsible for administering it. The Standard Patents in Australia have a maximum duration of 20 years (or 25 years for a pharmaceutical patent). An innovation patent has a shorter term of up to eight years from the date of the patent. However, this type of patent is being phased out by the Australian Government. Existing innovation patents will remain valid until they expire on 24 of August 2029. No matter the type of patent, the invention must be disclosed in a specification that describes the invention and ends with claims that define the scope of the patent monopoly. The invention must be new and qualify as a manner of manufacture in the legal sense. The invention must also have an inventive step. The specification must be clear and not vague and the claims fully supported by the information in the specification.

Design

The Designs Act 2003 is a law that protects the appearance of products. For a period of up to 10 years, the law provides an Australian subsidiary exclusive rights to use, manufacture, and sell the design in Australia and legal protection against businesses that infringe their design. Businesses can register their designs with IP Australia, the Australian government agency responsible for administering IP rights in Australia. The application process is relatively simple and can be done online. Any company that owns a registered design must mark products with the design registration number.

Copyrights

The Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) grants exclusive rights for specified actions concerning works and other subject matter throughout the duration of copyright in Australia. Unlike patents or trademarks, copyright doesn’t require registration; it automatically exists in qualifying works or subject matter. Australia, being a signatory to the Berne Convention and Universal Copyright Convention, reciprocates recognition of copyright from other signatory nations. Overseas works are regulated through the Copyright (International Protection) Regulations 1969 (Cth).

For copyright protection, the work must be original and in a material form. Originality implies human authorship and a degree of skill and labour in creating the work. Other subject matter must be original, not a direct copy of a prior recording, film, broadcast, or edition. Upon meeting these criteria, copyright automatically vests in the owner, who can transfer rights except for moral rights, which are personal and non-assignable. Copyright in Australia generally persists until 70 years after the author’s death, except for TV and sound broadcasts (50 years from the first broadcast), Sound recordings and films (70 years from publication) and Published editions of works (25 years from publication).

Circuit Layout Rights

The Circuit Layouts Act 1989 (Cth) safeguards the original designs of circuit layouts, defining these layouts as the specific patterns of electronic components and connections within integrated circuits. This Act establishes a framework allowing businesses to safeguard their circuit layouts and outlines the rights and responsibilities of layout owners. A circuit layout receives protection only if it’s original and holds a connection with Australia or a foreign country specified in the Act’s Regulations. The originality criteria are higher than copyright law but lower than designs law, demanding a creative contribution by the maker and a layout that isn’t commonplace at its creation. When protected under the Circuit Layouts Act, the owner gains exclusive rights to copy the layout in material form, manufacture an integrated circuit based on the layout or a copy, and commercially exploit the layout within Australia. The rights regarding eligible layouts last for a term of up 20 years.

Plant Breeder’s Rights

The Plant Breeder’s Rights Act 1994 (Cth) is a law that protects the original varieties of plants and fungi. It provides a framework for businesses to register and protect their plant varieties, and it also sets out the rights and obligations of plant breeder’s rights owners. By registering a plant variety, the owner has the exclusive right to produce, reproduce, propagate, import, and sell the plant variety in Australia. This means that other businesses cannot exploit the registered plant variety without the permission of the owner. The Act also allows for the owner to protect derivative plant varieties that are based on the original variety. Plant breeder’s rights typically last for 20 years for trees and vines, and 25 years for other plants.

Superannuation Guarantee Charge

The Superannuation Guarantee Charge (SGC) is a penalty imposed on employers who fail to pay their employees’ Superannuation Guarantee contributions on time and in full. The consequences of not paying super to employees can be severe, both financially and reputationally. Businesses should take all necessary steps to ensure that they are complying with their SG obligations. The SGC is calculated as follows:

- Shortfall amount: The amount of Superannuation Guarantee contributions that were not paid or paid late.

- Interest: 10% per annum on the shortfall amount, calculated from the due date of the SG contributions to the date of payment of the Superannuation Guarantee Charge.

- Admiration: $200 per Superannuation Guarantee Charge statement.

The Superannuation Guarantee Charge (SGC) is not tax deductible, which means that businesses cannot claim it as a business expense. This can significantly increase the cost of non-compliance with SG obligations. In addition to the SGC, businesses who do not pay Superannuation to their employees may also face other penalties, including:

- Penalty 7: A penalty of up to 200% of the SGC.

- Tax evasion prosecution: Criminal charges for tax evasion, which can result in imprisonment.

Doing Business in Australia with BridgePoint Group

We offer a comprehensive solution. From corporate structuring and tax advice, employing and remunerating staff, local representation to maintaining systems of control and reporting. We help you to successfully navigate the regulatory and operational landscape. We are familiar with Standard Business Reporting (SBR); Significant Global Entities (SGEs); Country-by-Country Reporting (CbC); Transfer Pricing; Thin Capitalisation; Single Touch Payroll (STP) and Director Identification Numbers.

We provide advice in respect of the Corporations Act, Trade Practices Act, National Employment Standards, Fair Work Act, Trade Marks Act, Privacy Act and the various State and Federal acts relating to taxation including Income Tax, Capital Gains Tax, Payroll Tax, Land Tax, Goods and Services Tax (GST) and the requirements to withhold tax from payment of dividends, interest and royalties.

We regularly interact with the Australian Taxation Office (ATO), Australian Securities and Investment Commission (ASIC), the Foreign Investment Review Board (FIRB), the Australian Competition & Consumer Commission (ACCC) and various State Revenue Offices around the country.

What makes us different

One stop shop

We offer a comprehensive and holistic approach to supporting international companies – including Significant Global Entities (SGEs) – in their expansion efforts, ensuring a smooth entry into the Australian market whilst carefully navigating the complexities of local regulations and business practices.

Local Knowledge and Market Insights

Venturing into a new market abroad can entail considerable expenses, time, and risks. Our dedication to clients extends beyond offering accounting and regulatory services. We provide comprehensive support by offering market insights and local assessments, empowering you to make well-informed decisions.

Unique Method

We employ a team-based, cross-functional approach to ensure you get the full benefit of our collective capability.

Results-Driven

We partner with our clients with an owner’s mentality.

Commercial Acumen

We understand the drivers of your success and help you to tackle the things that make the difference.

Broad Capabilities

We have a diverse team of highly trained experts selected to support every stage of your business journey.

What to expect from us

- A highly experienced team that will tell you everything you need to know about doing business in Australia.

- Clarity about obligations when employing and paying people in Australia including PAYG withholding, reporting, payment, superannuation and workers’ compensation insurance.

- Corporate structuring advice and establishment.

- Taxation advice and registration including ABN, TFN, FBT, Payroll tax, PAYGW and GST.

- Opening a local bank account.

- Local knowledge and representation including directorship, ATO, ASIC and OSR agency.

- Advice regarding the Tax Act, Corporations Act, Trade Practices Act, Privacy Act.

- Selection of compliant accounting software.

- Preparation of management reporting packs.

- Ongoing advice and support including pro-active communication.

We assist overseas headquartered companies to achieve a smooth entry into the Australian market whilst carefully navigating the complexities of Australia’s legal, regulatory and commercial environment. Our services are built on the strong foundation of a deep understanding of the numbers, with accounting, finance and business strategy at the core.

If you would like assistance in setting a business in Australian, or to find out more about the benefits of doing business in Australia with BridgePoint Group, download the complete Doing Business In Australia Guide here or contact us directly.